Nine months into the pandemic, major tabletop convention organizers — the Gen Cons and PAXes of the world — have failed to bring their events online in a way that approximates their real-world magnificence.

Nine months into the pandemic, major tabletop convention organizers — the Gen Cons and PAXes of the world — have failed to bring their events online in a way that approximates their real-world magnificence.

The challenge is monumental, and there’s only so much point in criticizing the moon for being far away. But in scrambling to make their events happen, organizers haven’t taken enough time to think through what’s critical about the experience they provide. The result is that they’ve mostly rushed to adapt each individual event to the online environment, and conducted this process en masse. But in tackling virtual adaptations individually, they haven’t taken into account the key factors that unite those events and spaces into a convention. And so they’ve left behind what it is about those assemblages that almost compels people to love them.

Conventions are Control

A key service — maybe the key service — a convention provides is to isolate you from your regular daily obligations. Not only that, but to make it socially appropriate for you to set those obligations aside for the duration of the con. A convention’s programming is secondary to the freeing permission it bestows.

Why would we value this so highly? Because the most devilish conundrum of most gamers in their working lives is not their work itself, but how to organize and prioritize it. Most folks are trained for, talented at, and interested in the substance of their work. Conversely, almost no one is formally taught to mindfully structure their tasks, to set and revise their priorities, and to actively burn down the distractions that are everywhere and always all around us. Most days, it would be better to make progress on the right thing than to entirely finish the wrong thing. And yet most days, many of us get this calculus wrong.

The fact that we all burn so many brain-cycles trying to simply figure out what to do with each moment of our days helps explain the subconscious attraction of conventions. The spaces and times within the boundaries of the con experience — the airplane, the hotel room, the convention center, the events, the games, the meetings — are spaces and times where not only are your priorities exceedingly clear, it seems irresponsible not to give in wholly to their demands. You spent $500 on a plane ticket. What fool would answer emails, draft marketing copy, or re-write a rulebook instead of networking, taking meetings, playing prototypes, or standing in the exhibit hall booth or hotel bar awaiting the next serendipitous meeting? Not to mention that so many distractions become flat impossible the moment you close the door to home behind you. You can’t very well mow the lawn or put the kids to bed when you’re not even at home. And it feels good to have the sense that you’re doing the right thing, and to have your immediate physical tabletop game convention world support the idea everywhere you look.

General-interst virtual conventions can’t provide this visceral detachment from your thrice-accursed to-do list, and they can’t give you meaningful cover from your other obligations. Or, at least none seem to have figured it out yet, although some more focused events — pervasive online LARPs, particularly — seem to be making progress.

Can virtual events do something, anything, to address this issue? Probably! For one thing, they could be extremely clear in defining the blocks of time they’re laying claim to. Gen Con is the best four days in gaming, but simply listing the days on which a virtual convention takes place is suddenly and surprisingly insufficient, because car trips and airplane tickets aren’t there to do the physical work they’ve been quietly doing all these years to concretely mark the beginning and ending of the convention experience.

The conventions that have charged for event tickets have also made progress on this front. When one spends money, one blocks the time to defend the investment.

Virtual events could also aim to be very circumspect about the blocks of time they ask for. It’s easier to ask a con-at-homer to set aside five hours than five days.

Virtual conventions should take mindful pains to help guide people through the logistics of blocking off and defending their con time. This could be as modest as simply asking people to think ahead about it. Vrbo emailed me a ten-item list of things I should do before I leave home this coming Sunday; a convention could do something similar. (“We see you’re planning to attend our worldbuilding panel at 5:00p Central tomorrow! Did you mark yourself busy on your work calendar? Is your Zoom install up to date? Are your earbuds charged? What will your kids be up to?”)

Conventions could, with thought and resources, go further. It wouldn’t be terribly difficult to generate calendar invites for convention events, as just one very low-hanging example.

In a conversation where I proposed this theory about how conventions mostly serve to block time, a number of folks mentioned that their number-one convention love is the serendipitous opportunities that cons provide to meet people. And yes! Conventions are like slot machines of social interaction. Bored? Head to the hotel lobby and spin the reels again! You can meet tons of new folks and run into old friends and acquaintances in a constant cycle.

This is also blocking time. The con has cleared everyone’s schedule and made it appropriate to spend 20 minutes chatting with the folks that run the game store in Cambridge (instead of shoveling the driveway), or an hour having dinner on three minutes’ notice with friends-of-friends you just met (instead of working out). These things tend not to happen in our everyday lives because our everyday lives are packed.

Less Impossible, Still Difficult

It may simply be impossible for online conventions to effectively command their attendees’ time. But two other key features of traditional conventions are also crucial to their success. (And neither one of these is programming, either.) While these qualities are also difficult to bring online, they are less flat-out impossible. Even so, they won’t appear by accident, so tackling them proactively is the challenge for tabletop con organizers.

The Power of Moments is an insightful and useful book by Chip Heath & Dan Heath. If you haven’t read it, you should. It’s devoted to explaining why certain experiences have outsized impact in our lives.

The book offers four reasons that certain experiences are impactful. The two that I think are relevant here are elevation and connection.

- Elevation. Impactful events transcend our everyday lives in ways that are concrete and obvious. Super Bowls, job promotions, moving to a new apartment, going to Essen.

- Connection. Impactful events are social, accumulating importance because they’re shared with others. High school and college graduations, wedding receptions, family vacations, years-long D&D campaigns.

Of course there were balloons at Gen Con’s 40th anniversary. Photo by Christine Garrison (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

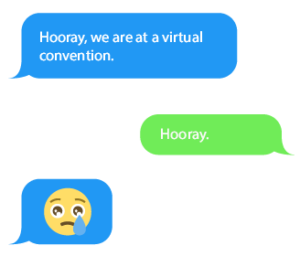

By these measures, virtual conventions are relatively sad reflections of the real deal. They don’t transcend everyday life because they happen in the exact same places, and they use the exact same tools, as everyday life. Although it might be possible to craft a socially connected virtual convention experience, I don’t feel like anyone has figured it out yet. While everyone’s copious experience with social media and playing MMORPGs demonstrates that it’s possible to create social connections virtually, those examples don’t create connection at the fast-forward, four-day speed of a con. Certainly not in a way that doesn’t boil down to a more frustrating version of the platforms that were available before the convention started, will be available the entire time it’s running, and will continue to be available after it’s over. (“Come meet people at our virtual convention! It’s like Facebook, except you start over with no friends!” Sad trombone.)

To succeed at virtual convention organizing, teams must give as much or more thought to elevating the experience and connecting attendees (quickly! In functional and meaningful ways!) as they do to adapting their programming. Virtual spaces can (must!) be crafted with intention to work well. The default installation of any given piece of software is probably not the best one for every — or any — event.

Split Off and Focus to Expand

One mistake, I fear, has been the idea of taking a whole convention’s slate of business and nonsense online, altogether, all at once. The key problem with a digital platform that invites everyone to do everything — the way Gen Con successfully invites everyone and does everything in the real world — is that that already exists in the digital world. It’s called Facebook, it never goes to bed, and it has an overwhelming advantage of money and momentum over even the mightiest conceivable virtual convention.

The answer is to stop fighting Facebook, spin 180 degrees, and tailor the virtual event so narrowly that two things happen:

- Only a very small number of people care about it, and

- Every single one of them would rather die than miss it.

Not an online game convention. Not even an online roleplaying convention. An online event for fans of Rolemaster. (And maybe not even every Rolemaster fan — maybe only fans of the third edition need apply.)

Not an online distributor open house. Not even an open house for stores that sell Magic: The Gathering. Perhaps an online event for stores that need to figure out how to right-size their CCG singles inventory by the end of December.

Not an online costume contest. An online costume contest for dogs dressed up as Gandalf.

That is: The road to success may lie in cutting discrete events out of the whole, and then hyper-focusing them in order to expand their (sub)audiences. In doing that, organizers ask less of those folks while simultaneously getting them extremely excited about the things they love the most.

More focused events have additional advantages for organizers in that they are less likely to require expensive or bespoke web platforms. They can use Slack, Discord, Zoom, Eventbrite, Shopify, and a hundred other existing pieces of Internet infrastructure instead of requiring the mass adoption of some ConventionOS that’s trying to be all things to all people while it tries to run equally inside every desktop and mobile web browser in the world. (Yuck!)

Smart organizers would figure out which synergies apply best to categories of focused events. Each individual event would absolutely require its own domain-obsessed shepherd in any case, but the wider administrivia and infrastructure are probably more universal, and might work for multiple events, whether parallel in time or spread over a longer period.

A few months ago, I attended a game design speed pitching event called NonePub. It’s a perfect example of what I’m proposing here. If you’ve never been to an event like this, it’s sort of a sales festival where a dozen or so designers pitch their games to a dozen or so publishers, in a series of one-on-one meetings, each lasting five or ten minutes, over the course of about two hours. Speed dating, but for designers and publishers instead of lovers.

NonePub was such a dramatically better experience than any similar in-person event I’ve ever been to that I never need to go to an in-person pitch event ever again. In fact, the next time we have Gen Con in person — which I am really, really looking forward to — it will be a better convention if its speed pitching event takes place online instead of in person, on some weekend that is completely different from the main con’s “best four days in gaming.”

Why was NonePub better online? I’ll unpack it.

Many in-person conventions have speed pitching events. But the only reason these events need to take place at conventions is that conventions are the places where the relatively small number of people who want to attend events like this find themselves.

Other than the people all being there, conventions are not good places for these events. At in-person speed pitching events, publishers are traditionally exhausted from the get-go. Most stood in a booth all day, rushed to dinner (which might have also been a meeting), and then rushed to the pitch event. There, they were called on to focus, quickly understanding and then also commercially evaluating the intricacies of a dozen different game designs, one after the other. Conversely, at NonePub, I had a regular day, ate dinner at home, and logged onto Discord in the evening to do that stuff.

Nor are the physical settings for the in-person pitch events great. They take place in hotel ballrooms at infinite rows of rectangular tables. Everyone’s talking at once, so it’s hard to hear, and hard on your voice. Each time however-many minutes have passed, the publishers get up and move to the next table, and the designers frantically reset their prototypes for the next pitch. Conversely, at NonePub, rather than physical prototypes, designers screen-shared digital versions, mostly using Tabletop Simulator and Tabletopia. They could reset presentations with a click; instantly load starting, mid-game, and endgame game-states to answer questions; and even switch to pitching completely different designs without having to clear the table and reset a different physical prototype. It was great.

Of further benefit: There were designers (and publishers) from everywhere. Not everyone can travel to an in-person event. It takes time, means, and mobility. These limits were dramatically reduced at NonePub compared to similar events embedded at Origins, GAMA Expo, and Gen Con. It’s easier to move electrons than humans.

One Thousand Possible Futures

General-intrest virtual tabletop conventions have not succeeded. At least, not by any measure I’d feel good about as an attendee, organizer, or investor.

The good news is that the online environment calls for something different. Truth be told, it calls for something simpler. Or, rather, a thousand somethings simpler. Or ten thousand.

In this environment, it won’t be as easy for the existing players to rake in the pots of cash they’re accustomed to making. Let a field of single-tear emoji bloom, and let mine be the first: 😢.

What we’ll get, instead, is the chance to meet up, for an hour or two, with the two-dozen other folks from across the world who wore out their own copies of Arms Law in the early ‘90s, or who want to play a LARP created by their very favorite designer, or who are desperate to learn how to deal with VAT while fulfilling their Kickstarters. I’ll attend them all, if someone can just help me get my to-do list under control.

—

Thanks to Jason Morningstar and Seppy Yoon for their valuable insights on earlier drafts of this article, which helped me improve it a great deal. Message bubbles graphic template designed by Freepik.